It was a time of knights and kings.

It was a time of civil war.

It was also the time of William Marshal, a breed of knight that at that period seemed only dreamt of in Geoffery of Monmouth’s tales of King Arthur. Proclaimed by both friend and foe as the greatest knight who ever lived, William Marshal has become a forgotten historical character who was at the center of many actual events from this period. Standing at a towering six feet two inches, William would prove to be the envy of his peers. He served as an officer and Marshal for four kings, dilivering the colée (the knighting blow) to King Henry the Younger, son of Henry II, as well as being the young king’s mentor. William was also the only man to unhorse Richard The Lion Heart.At the age of 75 (when most men of that time died by 35) William lead the English army against invading forces from Normandy at Leeds Castle and killed the invader’s leader, an officer 35 years his junior, in personal battle. Before William’s death in 1219, he was made Regent of England over the child king, Henry III. He accepted the office of Regent only after the Pope promised to absolve William of his sins as a warrior. On his deathbed, William was enducted into the Templars.

William Marshall Timeline

1135 – Death of Henry I and the taking of the throne by his nephew Stephen.

1139 – The year that the daughter of Henry I, Matilda, invades England, declaring a challenge to Stephen’s crown. John is Stephen’s Marshal.

1144 – With no actual birth records, this is the estimated year of William’s birth and possibly the time around which John Marshal turns his allegiance from Stephen to Matilda.

1152 – The seige on Newbury Castle where Stephen holds William hostage and the battle that leads to a treaty between Stephen and his daughter. In a dramatic moment, Stephen prepares to hang young William because of John Marshal’s treachery. John told the King to do as he pleases, “I have the hammers and the anvils to forge still an even finer son”. Angered, Stephen allows his generals to take the boy out to the noose, but as they are about to hang the boy, Stephen personally carries the young William to safety, promising that young William will never come to harm while in Stephen’s care.

1153 – The year the treaty is signed.

1154 – Stephen dies and Henry II rules as King. William is returned to his parents when Stephen dies.

1156 – William is sent to Normandy to be educated as a knight by his politically powerful cousin William of Tancerville, Chamberlain to the Duke of Normandy. William wept at saying goodbye to his mother, brothers and sisters. No record of his father being present at his leaving is written of.

1164 – William is knighted finally. The ceremony took place during an episode in the war between Henry II of England and Louis VII of France, when Henry called upon William of Tancarville to assist his ally, Count John of Eu. Meeting Count John and William de Manderville, Earl of Essex, at Drincourt (now Neufchatel-en-Bray), northeast of Rouen, the Lord of Tancarville decided to knight William in anticipation of the battle. During the melee, William breaks his lance, loses his horse but fights to free the village. The villagers cheer him on as he, nearly alone, cuts his way through the French army that block the street. His cousin from Tancarville weeps the tears of pride as he sees his young cousin; he says, “Look! Look at William! He fights to deliver the town rather than to take prisoners!” Another argues, “He takes no ransom, my lord. He will have nothing.” The older William cuts the other off, “He is the only knight in battle this day.”

1165 thru 1166 – William travels and practices the art of battle in the tournament. He wins his first tourny, but when the heralds seek him out, they find him at the blacksmith’s shop, having to have his helmet removed. It had been hit so many times and beaten so tightly onto his head that it has threatened to kill him. After this, he remains undefeated in battle and shows other knights and nobles the true meaning of chivalry.

1167 – Young William returns to England where his father and stepbrothers Walter and Gilbert have all passed away. William’s only brother, John, holds the family office of Marshal for the King. William, not wanting to sojourn, meets up with his uncle Patrick, the Earl of Salisbury, to suppress a revolt in Poitou. In an ambush near Lusignan, William’s uncle is killed. Severely wounded himself, William is taken prisoner. Eleanor, Henry II’s Queen, pays the ransom for William. William, the battle was lost, is revered now and recognized as a gallant knight by even the King himself.

1170 – Henry II crowns his eldest son, also named Henry, as a king. Henry II also names William as head of the new young King’s household as well as being placed in charge of his military training. Astonishingly, the young King was much into being a knight, and receives the knighting blow, called the colée, from William himself.

1174 – The young King and William separate after rumors of William and young Henry’s Queen are maliciously spread by envious knights. William travels through Europe, beginning 12 years of knight-errantry and a successful participation with the tourny.

1177 – William partners up with the Roger de Gaugi and both are undefeated in the tourny.

1179 – After demanding the right to prove his innocence before both Henrys, William finds himself frustrated again when they state no contest. He leaves after giving a great speech on the injustice he feels. The young Henry releases his Queen back to her brother, Philip of France, and begs for William to return. William rejoins the young King’s household, continuing to fight in tournaments. Philip II is now King of France.

1183 – After a tourny, William receives word to rush to meet young Henry. While enroute to the young King, William happens upon a young man and woman, who are in fact a monk and a girl who have eloped. This disturbs William some. But he is enraged when he hears the young man say he plans to lend out his money for profit. He proclaims, “By the sword of God! I don’t care what you two do with one another. Your sin remains between you. But by God, a man of the cloth enacting the sin of usury?! This will not do!” and takes their money from them and divvies it up with the two other soldiers traveling with him. Upon his arrival to the household of the young King, he discovers young Henry has taken seriously ill. Now on his death bed, the young King, who has just taken his Crusader’s vow, requests William to take his Crusader’s cloak to Jerusalem and place it on the Holy Sepulchre. After the young King’s death, his father, Henry II, gives William two fine horses and money for the journey to the Holy Land.

1184 thru 1186 – William remained in Syria where he fought alongside the revered Knights Templar. They found him a man of true chivalry and courage. Being one of the few outsiders accepted into the ranks of the Templars, this relationship in Middle East would serve later in his relationship with the Templars.

1187 – Returning to England, Henry II request the service of William. But the household is full if treachery. Henry’s sons, Richard, Geoffrey and John are constantly at odds with their father. In one attempt to take his father hostage, Richard hears that his ill father is traveling from Chinon. Not using his wits, Richard launches off to take his father, but forgetting his weapons. William sees Richard and is enraged at the youth. Richard, realizing his mistake all but too late, cries out, “By God’s legs, Marshal! Kill me not, that would be wrong for I am unarmed!” William, whose sense of honor as a knight is equaled only by his sense of justice, runs his lance through the neck of Richard’s horse, sending Richard head over heels onto his ass, calling out to the young Prince, “No. Let the devil kill you this day, for I shall not!” So impressed by William, Henry II promises to William the hand of Isabel de Clare, the 18-year-old daughter of the Earl of Pembroke. Owning this property in Wales and Ireland could finally offer William, for the first time in his life, a position of wealth. He also discovers love with Isabel. John d’Erley becomes William’s squire.

1189 – Henry II dies. Richard attends the royal funeral. Now King, of all those whom sided with his father against him, he calls upon William to meet with him and his royal counsel privately. His first words were to William, “Marshal, the other day you sought to kill me, and dead I would surely be if I had not turned your lance aside with my arm. That would have been an evil day for you.” William returned, “Sire, I had no intention of killing you, nor did I ever try to do so. I am still strong enough to direct my lance. If I had wished, I should have struck your body, as I did not do so by mistake, nor do I repent doing so.” Richard studied his remarks and replied, “Marshal, I pardon you. Never shall I bear you rancor for it.” This was to William’s relief. Then one of the other generals says of the Lady Isabel, “Might I remind you sire, that your father gave her to Marshal.” Richard, knowing that the gift was over William’s defense of Henry from Richard, answered sharply, “By God’s legs he did no such thing. He but only promised to do so,” Then he calmly added, “But I will give her to Marshal freely, both Lady and lands.” Richard then oversaw the marriage of William and the young Isabel. William was now a general for Richard as well as the earl of Pembroke.

1193 – With help from Philip of France, Prince John seizes Windsor Castle in an attempted coup for the throne while Richard is being held captive for ransom by Germans. William lays siege on the castle and holds John and his troops at bay until Richard’s release. John takes flight to France.

1194 – While Richard went off to battle in Syria and Europe, spending little to no time at all in England. William’s relationship with his new bride flourishes. Then William’s brother John dies. William is now appointed to the office of Marshal.

1197 – Leads an army for Richard and captures the castle at Beauvais.

1199 – In January Richard is mortally wounded in a battle at Chalus-Chabrol by a crossbow bolt. His last official command before dying is to have William made Custodian of the Royal Treasure.

1210 – In a common tantrum, John makes a claim that William has acted in some treasonous manner. William, who counts only one thing above his duty, and that is his honor, throws his gauntlet down before the King. When the King doesn’t respond, he challenges any knight to pick the gauntlet up in the name of the King. None do so. His honor restored.

1215 – With sympathies with the barons but loyalties lay with John, William rode with the King to Runnymeade for the signing of Magna Carta. While William signs on behalf of the royal court, his eldest son signs on behalf of the barons.

1216 – In the Fall, John dies and makes William Regent of England until his son Henry is old enough to reign. It is only after the Pope promises that William will be forgiven for the many that have died at his hands, that William will accept.

1217 – Philip orders the Count of Persche to lay siege on Lincoln Castle near Dover. They successfully take the region, but William, defending the crown of the new young king, leads the army into battle at the age of 75. He spots Persche during the battle and, while he really wants to capture the Frenchman, the younger French officer makes a fatal mistake in trying to trade blows with William. William ends up killing Persche when a splinter from his lance pierces Perche’s skull through his helmet.

1219 – on Tuesday, May 14, William Marshal, once Earl of Pembroke, Marshal to four kings, Protector of the Royal Treasury, and finally Regent of England – succumbs to death after a long illness. When word reaches the palace of Philip of France, he openly weeps, declaring that the Marshal was the true flower of chivalry.

1241 – All sons and direct male descendents of William Marshal whom could carry on the Marshal name are dead.

William Marshall Childhood Years

The Childhood Years

Though archeologists have debated over the “Newbury Castle” referred to in the biographical poem about William Marshal, Donnington Castle (shown here on the left) in Newbury, England may well be the location of the battle between King Stephen and John Marshal.

It was a time of civil war.

King Henry I has been dead since 1135.

Stephen, Henry’s nephew, quickly claims the throne over the direct heir, Matilda, daughter of the dead King. Stephen’s favor with the subjects solidifies his usurping of the throne. But after a few years, Matilda invades England and finally contests Stephen’s throne stating she was the legitimate heir.

But she finds her claim is not popular with the subjects. This doesn’t end the conflict. A civil war was now underway.

A rub for Stephen now also lay in the tear between the barons over him and Matilda. A tear that ripped into his royal counsel, when his marshal, John Marshal, turned to Matilda’s side.

During this war, young William was born. Scholars guess his birth year around 1144 (There is no record of his birth and William was never sure himself).

When young William was about 8 years old, he found himself at the center of this civil war. Stephen, still holding a grudge against John Marshal, had cornered the man and his troops at the Newbury Castle. John had called for a truce with Stephen, promising to discuss giving the castle to Stephen, but he would instead attmpt to regarrison the castle. Stephen had taken in exchange for the first truce, young William Marshal. After being betrayed again by his former marshal, Stephen informed John that he would hang his youngest son at dawn if he didn’t surrender the castle. John’s response, as reported by Jean d’ Trouvier, was quite a shock. “Do as you will,” The elder Marshal said. “I have the hammer and anvil by which to forge still an even finer son.”

Stephen, who had become very fond of young William, playing out battles with the boy using sticks for swords and lances, was now preparing to execute the boy. By dawn, he allowed one of his knights to escort the boy to the makeshift gallows. But before he is killed, Stephen carries the young William away in his arms saying, “You shall never come to harm by my hand William, this I swear.” And though his officers planned to catapult the boy against the castle wall, Stephen intervened and protected the boy. Soon a treaty was signed between Matilda and Stephen that would have her son, aptly named Henry, be Stephen’s heir to the throne. Within a year, Stephen was dead… of natural causes.

William, by now a page, was ready to become a squire. Young boys, especially the youngest in a knight’s family, were somewhat in the way and not useful. So William found himself being shipped off to Normandy, to his cousin, William of Tancarville, to be trained in the ways of the knight. It has been said that William wept at his departure from his siblings and mother. It is also said that William’s father was not present at his going abroad.

Within a short time, William was among many other boys his age. His lord cousin was very fond of young William. In fact the boy used to get the choicest cuts of meat from the stews, even before the lord of the manner himself had been served. Many of the boys were jealous, and even complained of his long sleeping habits. But the food and sleep were all part of something young men really didn’t suffer from at the time. Growing pains. Most grew to about five feet six inches, the average height of a man at the time. William was now well up to over six feet by his mid teens. The food and sleep was all part of his growing. It is about this time he picked up his nickname “William Wastemeat”.

William, though still a boy, is a natural with weapons, and as a squire he excelled. With great dexterity, he mastered every weapon. But, in his late teens (or perhaps 20), on the eve of battle, it would be here that William’s squire years would come to an end.

The Knight Errant

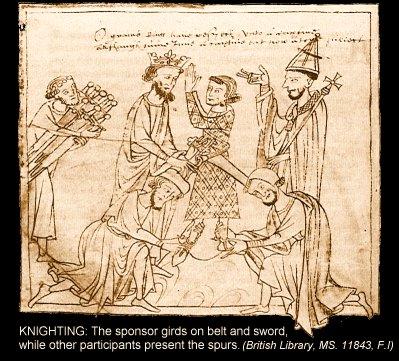

It was the eve of battle and young William Marshal, all but 16 years old (scholars, due to the lack of an actual birthdate, speculate that William’s age range was between 16 to 20), was in a rushed ceremony for his knighthood. His cousin, William of Tancarville, delivered the colée (the knighting blow of the sword) and then gave as a gift to young William his finest horse.

Then, with his elder lord and cousin, William and fellow knights defended the village of Drincourt. When most knights fought for ransom or finance at the time, young William, to the cheers of the village, fought for it’s freedom. His lord cousin watched in awe, pride swelling in his chest, as he saw young William charge forward, his steed was cut out from under him, rising to the battle, with broken lance in one hand and his sword in the other. William took lead in the charge, and drove the attack against the enemy army. His cousin was moved to tears, stating that, William fought like a true knight; not for reward, but for the liberation of these people.

Though quite heroic, later his acts would come to haunt him. While at a feast celebrating the victory, his cousin asked if William had a gift for him, as was custom at the time. William proclaimed, “Surely what?”

“A crupper, or a horse collar?”

The Marshal of England

This part of William’s life is of the greatest transition. Now nearly fifty, William has earned the respect of the people, knights and kings as a great warrior knight. But as soon as he weds Isabel, the damsel of Striguil, only the second richest heiress in all of England, William left the world of Knight-errant and entered what would be today, the world of politics. But politics of William’s day had a bloodier outcome if it got ugly.

It was 1189, Henry II was dead and Richard was King, though the coronation hadn’t officially taken place, and William was seen leaving Paris “riding off at a breakneck speed ” to take possession of his bride to be. Before leaving, as part of Richard’s royal counsel, William was instructed to go to England and guard Richard’s lands and rights. During his crossing of the channel, the deck broke under his feet and William broke his leg. Without hesitation, he finishes his trip, and crosses to England, stopping to pay a call on the newly married Queen Eleanor. Once in London, he meets with resistance from Isabel’s guardian, who at first is combative with William, but with threat to his life and limb, releases Isabel to William.With blood like fire, William “burns” for Isabel, wishing to deflower her immediately. But the wedding must take place on the land that she had inherited, knowing that her family was jealous of someone outside the bloodline taking the land. Showing affirmation, and great celebration to boot, the wedding took place. Then William, in a local inn, took his wife — having to borrow a bed from a friend, Sire Engerrand de Abernon to do so.The day had finally come; William Marshal was married, the owner of a vast estate and several fiefs in Ireland. He was no longer a knight-errant. He was now Earl of Pembroke.

It was 1189, Henry II was dead and Richard was King, though the coronation hadn’t officially taken place, and William was seen leaving Paris “riding off at a breakneck speed ” to take possession of his bride to be. Before leaving, as part of Richard’s royal counsel, William was instructed to go to England and guard Richard’s lands and rights. During his crossing of the channel, the deck broke under his feet and William broke his leg. Without hesitation, he finishes his trip, and crosses to England, stopping to pay a call on the newly married Queen Eleanor. Once in London, he meets with resistance from Isabel’s guardian, who at first is combative with William, but with threat to his life and limb, releases Isabel to William.With blood like fire, William “burns” for Isabel, wishing to deflower her immediately. But the wedding must take place on the land that she had inherited, knowing that her family was jealous of someone outside the bloodline taking the land. Showing affirmation, and great celebration to boot, the wedding took place. Then William, in a local inn, took his wife — having to borrow a bed from a friend, Sire Engerrand de Abernon to do so.The day had finally come; William Marshal was married, the owner of a vast estate and several fiefs in Ireland. He was no longer a knight-errant. He was now Earl of Pembroke.

Out of great affection and possibly concern over losing his beautiful young wife to a younger suiter, William took Isabel with him wherever he went, whether to royal court or to battle.

During his reign as King, Richard spent very little time in England. So much of this period, William spent protecting Richard’s lands and assets as well as blossoming his relationship with his bride at the castle in Pembroke. But it was also during this period that John now plotted, with help from Philip of France, to steal the throne from Richard. Richard had been captured and taken hostage in Germany, being held in a pauper’s dungeon. Now, not unlike the tales of Robin Hood, John did try to take Windsor Castle. But it was NOT Robin and his Merry men that stopped greedy old prince John, but William Marshal, his knights and army that held John at bay until Richard’s safe return.

Still, relations between William and John were not all bad. Though William hated John, he knew he was a prince as well as King of Ireland. He would at times, while Richard was away, assist John in some of his needs.

This would later serve to help William gain some of his properties in Ireland he’d been promised.

In 1199, a message came to William that Richard was dead. Killed by infection from a crossbow bolt wound. Richard’s last official command was for William to be placed in control of the royal fortune, perhaps to keep John from immediately spending what was left. Richard, by funding his wars, had drained England into a financial depression. John would not have the fortunes to spend as was the usual for a king.

After he was crowned, England suffered many set backs. The barons, realizing the King’s financial woes, began to turn to Philip of France. John had been overtaxing them. England was on the verge of falling to the Norman crown.

John sends William and John d’Erley as emissaries to speak with Philip. He makes a deal with Philip for England, owing him a favor in return. John feels betrayed by this bargain, and claims William a traitor. William, who holds only one thing above his duty to the crown, his honor, answers the claim with a challenge, throwing down his gauntlet before King John. With an abundance of young knights eager for John’s favor, none take up the challenge to fight the old knight. The King retracts his claim and William’s honor is restored.

In 1214, with his loyalty to the crown, but his heart with the barons, William pushed for an agreement between the barons and John, knowing it would be the only way to hold England together. A location was agreed upon and John and his mesnie, including William, went to meet the barons at Runnymeade. There William signed along with John Magna Carta. William’s eldest son, also called William, signed for the barons.

1216 came, and King John took ill. Knowing that he is dying, he calls on the bishop to speak with William to take charge of John’s son, Henry, knowing that Henry is too young and inexperienced to be King. Honored to be asked, William declines. John d’Erley tells William this could help the country and all the knights and barons if he accepted, not to mention the almost St. Christopher-like duty he would have in bearing the young King on his shoulders. But William still was not convinced. Not until the bishop promised William that he would be absolved of all his sins, killing in combat, did William finally agree. For in this day, no God-fearing man would balk at absolution, especially one with the death toll that had fallen at William’s skilled warrior hands. John is relieved to hear William has accepted. On his deathbed, John makes his first act of contrition. In that he apologizes to all whom he has wronged in his life, William Marshall as the first and foremost of those whom he has wronged. With almost no one present, John dies quietly.

William is now Regent of England. With enemies all around, William leaves to protect the new young King. He travels to Malmesbury Plain, and finds the boy Henry in a sergeant’s care. When he arrives, the child greets William, weeping. He begs to be taken into God’s and William’s care. Everyone present weeps. Even William wept tenderly, holding him as if he were his own. William also realizes Henry may be a child but he was still King and had to have a sword. He dubs Henry, who was hastily fitted into a robe, and made “a knight small and fine” that day.

Soon, in Gloucester Cathedral, Henry had his coronation.

In the summer of 1217, Philip sent his son, Louis, to lead an invasion into England at Dover. With Count du Perche as his general, Louis attacked England. William, as Regent, decided to lead the battle against the invading forces.

The armies met in Lincoln.

There, outflanked due to his not trusting his Engish advisors, Louis and Perche are overrun. During the battle, William, now nearly 75 years of age, is seen charging at the head on his steed, without a helmet and looking like a knight half his age. So fast was his horse that he was quickly upon Perche, whom William wished to take hostage. But Perche decides to trade blows with William, a man nearly 35 years his elder. A splinter from William’s lance during the exchange slides over part of his helmet and pierces Perche’s left eye, killing him, making Perche’s death the only knightly death that day.

Honoring his relationship with Philip from years before, William escorts Prince Louis and his officers to a ship set for France rather than taking them hostage. This act by some was considered wrong, and later young King Henry III would refer to it as an act of betrayal. But, those who knew William also knew it was an act of honor and there was never any choice in it. The battle was won, England was safe from the invaders and William had been victorious in what would be his last battle.

He now returned to his duties as Regent as well as his duties as husband and father

The Final Days of William Marshal

After his return from the battle at Lincoln, William takes ill. It is a long and painful illness. It is now 1219.

He travels eventually to the Tower of London, where he has a favorite room, here he will now convalesce until his death.

His friends and family visit him here regulalry.

At his side until his death were his dearest and oldest friend John D’Erley, William’s wife, daughters and eldest son (William the younger).

The days leading up to William’s death are recorded in great detail. Conversations, times and events catalogued in British archives.

William would make an order for the poor to be fed with the money made from jewels and gifts that he alone had ownership of. He would leave nothing for his sons save the name and office. Though they stood to inherit much from their mother, William had actually owned little of his own and felt it a better honor that his sons have at life the way he had. And he deeply loved his sons, especially his eldest son William.

On his deathbed, William would also be given a great honor, being inducted into the Templar Knights. But to do this, he would have to release his wife and live out his remaining days as a monk. Loving her husband, Isabel released William from their bond. Though she stayed with him constantly for his long illness, William no longer “sought her out”.

It is now Spring.

William’s pain is worse. Cancer? Perhaps. His last day describes family, clergy, Templars all at his bed. Oh, and John D’Erley too.

At one point, William cries out, “By my soul, two men in white. They are beside me now. Never have I seen such fine men.”

John d’Erley is by his side and responds to him.”My lord, thus there comes to you a company that will lead you in the true way.”

“Blessed be the Lord our God, Who hitherto has granted me His grace. (With pain) John!”

“I am here for you.”

William now tells John, “John, make haste! Open the windows and doors. Call my son and the knights. I am dying. I cannot wait any longer. I must take my leave of them now.” William turns in the bed, and with great pain passes out.

William awakes to find all are in the room now, including Aimery de Sainte-Maure and Geoffrey of the Templar Knight order. Geoffrey has brought William’s crusader cloak.

“John, did I faint?”

“Yes sire.”

“I’ve never seen you look so helpless. Why haven’t you rinsed my face with rose water, so that I may speak properly to these good people? I have not much longer to do so.”

John gets the water and as William washes his face, for a moment he seems revitalized.

Now the man who has defeated every foe who has crossed his path says his last and final words: “I am dying. I commend you to God. I can no longer remain with you. I cannot defend myself from death.”

The clergy pray, and William makes the sign of the cross.

Then it is over, and William Marshal, a knight who served four kings as military advisor, Marshal and as Regent of England, is now dead. His eldest son, who has instantly become Marshal of England, weeps and wraps his arms about his dead father one final time. Though William never shared any love for or with his own father, this was far from the truth with William and his sons.

Geoffrey the Templar now lays the cloak over William’s still body.

The funeral is held over several days because there are so many who wish to mourn the knight. William’s body is moved from church to church during the services until its final resting place at the Temple church in London.

It was said that the poor were fed better by William the Marshal during his funeral than had been fed by any king.

And they wept for him.

When word reached France, Philip wept. He would go around to others in his court saying, “Have you heard? The Marshal is dead.”

The knight who was known throughout two kingdons as the flower of chivalry was dead.

But, not forgotten.

AFTERTHOUGHTS: William the Younger would hold the office of Marshal for several years until his early death in 1231. Then each brother, one by one, would take the office and would sadly die shortly afterward. First Richard, then three years later; Gilbert, who was a cleric, removed his cloak as a priest, put on a sword and took the office as Marshal in honor of his father. But he died from a fall from his horse in 1241. There remained only Anselm, whom the elder William had abandoned to his fate, judging that Anslem would, like himself as the youngest, have no chance of inheriting the office. Anslem’s fortune was brief: By 1245 he was dead. All brothers died leaving no male heirs, so there were no men left to bear the name Marshal or preserve the memory.

But, William the Younger, before his owen death, had hired a poet calling himself Jean d’Trouvier (John the Troubadour), who would pen an historically accurate and detailed one-thousand-nine-hundred and seventy-four line long poem that recorded William Marshal’s chivalric life. Though the mystery over whom the poet was, some believe, like myself, that it was none other than William’s ex-squire and knightly best friend for some four decades, John d’Erley. Either way, thanks to his prose, William Marshal, the flower of chivalry, lives on.

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Frances Gies – “The Knight In History” Harper Row (1984)

- Anonymous – “L’Histoire de Guillaume le Marechal” Penned by “Jean de trouver”, poem transalted by Paul Meyer. Paris: Societe de L’Histoire de France (1901)>

- David Crouch – “William Marshal: Court, Career and Chivalry in the Angevin Empire,1147-1219” New York: Longman (1993)

- Georges Duby – “William Marshal The Flower of Chivalry” Pantheon Books (1985)

- George Holmes – “The Oxford History of Midieval Europe” Oxford University Press (1988)

- David T. Zabecki – “A Knight Most Loyal” from Military History magazine (August 1987)

- Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson – “The Oxford Guide to Heraldry” Oxford University Press (1988)

- Geoffrey of Monmouth – “The Kings of Britain” translated by Lewis Thorpe, Harmondsworth, Eng. (1966)

- Britannia Website – “Histroy of the Monarchy” www.britannia.com

- [email protected] – WYRME’S ENCYLOPEDIA OF KNIGHTHOOD – www.free-host.com/wyrme/

This article is saved from archive.org and republished here as the original website has since gone offline.

Article by Gerry Kissell.